Background to some of the traditional handcraft

The Zulu nation is the largest ethnic group in South Africa and came into being in the early 19th century, when Shaka Zulu brought the more than 360 clans together, to form a single powerful kingdom. (Zulu: ‘heaven’ amaZulu: ‘children of heaven”).

The people of Zulu ethnic identity cherish their historic leader Shaka and the Zulu heritage is one of proud warrior status and attention to exquisite detail.

Living in what is today known as KwaZulu-Natal, (a province of South Africa), Zulu is largely rural people, though thousands have become businessmen and women or have entered other professions throughout urban South Africa. The culture and traditions of the Zulu people are immensely strong, deeply respected and remain little affected by western influence. The most sophisticated and highly educated Zulu person is still as aware of his/her Zulu cultural heritage as the rural pastoralist.

Traditional Costume and Dress

Throughout the year a number of traditional functions occur throughout the land of the Zulu. Zulu traditional attire made from skins, beads, and feathers are worn by men, women, and children.

Not so long ago it was possible to see such attire being worn on a daily basis, however today, daily dress is westernized.

In the deep rural areas, exquisite beadwork can still be seen adorned, much of it indicating the district from which the wearer comes.

The Unique Aspect of Zulu Beadwork

A beaded feature of traditional Wedding Blanket.

Traditional Zulu beadwork is often worn by Zulu women today as an affirmation of their cultural heritage. Their colorful beadwork is unique because of the eloquent way in which messages dealing with male-female relationships are traditionally woven into designs.

Ndebele beadwork, often sold on the streets and pavements of Pretoria and Johannesburg, is well known. Traditionally, certain beaded items were worn to distinguish young girls from their elder sisters, to identify girls to be engaged or to be married, or to celebrate weddings and and the birth of first children. Among the Xhosa of the Transkei, special beadwork is used to differentiate age and peer groups but distinctive decorative adornment is reserved for the bride , groom and their special guests at their wedding .

What makes Zulu beadwork unique, is the code by which particular colours are selected and combined in various decorative geometrical designs in order to convey messages. The geometric shapes themselves have particular significance and the craft itself forms a language devoted entirely to the expression of ideas, feelings and facts related to behaviour and relations between the sexes. Zulu love letters, an old art of sending messages through the skilled use of colours in a piece of beadwork is fast dying out. However, much is known and recorded about the skill of combining colours and designs. Moreover, these traditions persist in the form of products for sale . Zulu love letters and jewellery have been revived and tweaked in the form of commercial contemporary jewellery brooches and socially conscious items like HIV/AIDS pins.

Meaning of Symbols

Meaning of Symbols

The Zulu beadwork language is deceptively simple: it uses one basic geometric shape, the triangle, and seven basic colours. The triangle’s 3 corners represent the father, mother, and child. A triangle pointing down represents and unmarried woman; pointing up it represents an unmarried man. Two triangles joined at their bases represented a married woman, while two triangles joined at their points, in an hourglass shape, represent a married man.

Meaning of Bead Colours

The seven basic colours can be used to convey a negative or a positive meaning, as follows:

Black – marriage, regeneration sorrow, despair, death

Blue – fidelity, a request ill feeling, hostility

Yellow – wealth, a garden, industry, fertility thirst, badness, withering away

Green – contentment, domestic bliss illness, discord

Pink – high birth, an oath, a promise poverty, laziness

Red – physical love, strong emotion anger, heartache, impatience

White – spiritual love, purity, virginity (no negative meaning)

Zulu Grass Baskets

Zulu Grass Baskets

Basket weaving in KwaZulu Natal

Every basket is made of indigenous raw materials. The fronds of the Ilala Palm (Hyphaene Coriacea) are commonly used to weave this fine, watertight basket taking up to 1 month to produce a medium-sized piece. Young girls follow in the footsteps of their mothers and grandmothers and by the time they reach their teens, they are fully conversant in the age-old art of Zulu Basket weaving. In harsh economic conditions, such a skill provides much needed income for schooling and survival.

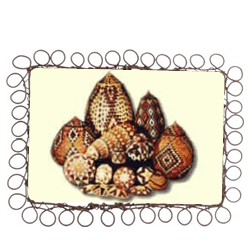

Examples of Traditional Zulu basketry

Zulu Baskets

Ukhamba (Zulu Beer Basket) is a bulb-shaped container rendered watertight by the tightness of the coil-weave, and generally used to serve sorghum Beer on ceremonial occasions.

Isichumo is a rigid, bottle-shaped basket used for carrying liquids, it has a lid, which fits over the neck like a cap.

Isiquabetho and Iqoma are open Bowls. The Isiquabetho is a large basin-shaped basket, traditionally used for gathering and carrying grain.

Nut Bowls and OOPS Baskets (Out of the Ordinary Production System) are tiny bowls traditionally woven by the Zulu children, who are taught by their mothers to weave from as young as 5 years of age.

Iqutu (Herb Baskets), The smallest of the Zulu baskets are not woven to be watertight, as they are used for the storage of dried herbs, for both culinary and medicinal use.

Canisters, straight sided storage baskets, useful for trinkets and nick-nacks are a more recent adaptation of the Ukhamba, using the same materials and patterns

Mbenge are small, saucer-shaped bowls used to cover clay Ukhamba in order to keep the beer insect and dust-free.

As with many Zulu artifacts, the humble Zulu beer pot has been raised to a new status of interior décor,

The use of the Zulu beer pot is an integral part of Zulu culture since ritual beer drinking takes place in every aspect of the customary Zulu life. In fact, King Ceshwayo claimed that beer was ‘the food of the Zulu’s’. Beer is used to introduce a new child to the family’s ancestors, at puberty ceremonies, at all marriage ceremonies as well as burial ceremonies. The beer is also used as a medium to evoke the ancestors – it is served in a pot and left overnight in the back of the hut for the ancestor.

Beer was even used as a form of economic exchange. It is the essence of hospitality and communality.

The beer is brewed and served in low-fired clay vessels. Three sizes are common: the large imbiza is used for brewing, the ukhamba (medium size) and the umancishana(small size) is used for serving.

Pots are also used for cooking meat, storing water and grain and for drinking sour milk.

Most Zulu pots are blackened after firing which is largely done for ritualistic purposes as the ancestors hide in dark and shady places. Over time, through their daily use, pots develop a warm, brown, glossy patina characteristic. The patterns and decoration on the pots vary according to family and region. These days’ contemporary ceramics have been inspired by traditional Zulu pottery. White pots with ethnic designs are a favourite décor item.

(extracts from Bona Africa)

The Zulu hat or |”Isicholos” originated from Kwazulu Natal stronghold of the powerful Zulu nation of South Africa. These hats are traditionally worn by married Zulu women for ceremonial celebrations. They are hand woven from cotton or rope or vegetable fibre, dyed with ochre and covered over a basket frame. Traditionally, they were worn on occasions such as weddings and funerals. Today however, they have been adopted as an iconic fashion item for many glamorous events such as the opening of our South African parliament, our presidential inaugurations and other events. They have also become a popular wall décor item and are even used as lampshades. While these hats are originally made from fabric, see our amazing version, created from a recycled tin can and wire.

Beads have been used worldwide since they first became available through trading – from Egypt as early as 1500 BC. Glass beads are a by-product of the discovery of glass, which occurred in Egypt during the rule of the pharaohs some 30 centuries ago. Egyptian glass beads were transported by the Phoenicians (1500-300 BC) from the Nile Delta to every port along the North African coast and the ancient Negro kingdoms of West and Central Africa. The Arabs succeeded the Phoenicians as traders and continued to supply beads to Africans along the East Coast. To this day, red cornelian beads of Indian origin are washed out on South Africa’s shores from ancient Arab vessels that fell victim to storms and sank.

Beadwork in Sub Saharan Africa has a much more recent history dating to the 17th century with the colonization of Africa by the Portuguese, Dutch and English. The Zulu people (or North Nguni) were offered glass beads by an English trader, Henry Francis Fyn who came to Port Natal (now Durban) in 1824. The South Nguni – of whom the Xhosas, Pondo and Thembu are well-known tribal groupings , located further south in the Transkei area of the Eastern Cape Province – had close contact with the British ever since the first settlers arrived in Delagoa Bay ( now Port Elizabeth) in 1820.

Glass beads were valued in Africa, not because Africans were duped into believing them to be precious stones, but because they were the products of an exotic technology, of which the equivalent was unknown in sub-Saharan Africa at that time. Beads therefore, became precious in their own right and were crafted into a variety of objects to be worn according to custom, and as a token of social status, political importance and for personal adornment.

Bamileke Hats from Cameroon

The Bamileke tribe was originally from an area to the north of Cameroon known as Mbam. In the 17th century, traders moved southward and currently reside in the grasslands of western  Cameroon. Today their population consists of about 8 million people. In Bamileke tradition, the Kuosi society, who report directly to the king, are responsible for dramatic masquerading displays.

Cameroon. Today their population consists of about 8 million people. In Bamileke tradition, the Kuosi society, who report directly to the king, are responsible for dramatic masquerading displays.

As shown, the Kuosi wear their impressive beaded elephant masks and feathered headressses.

This was formerly a warrior society, whose members today are made up of powerful, wealthy men. Even the king may don a mask for an appearance at a Kuosi celebration which is a public dance held every other year as a display of the kingdom’s wealth.

This was formerly a warrior society, whose members today are made up of powerful, wealthy men. Even the king may don a mask for an appearance at a Kuosi celebration which is a public dance held every other year as a display of the kingdom’s wealth.

Many of the artworks produced by the Bamileke tribe are associated with royal ceremonies. Most Bamileke statues represent the chief. Art objects showed the position of a person it the hierarchy. As a person descended or ascended the social ladder the materials used and the number of pieces changed. In a chief’s residence, one would find ancestral figures and masks, as well as headdresses, bracelets, beaded thrones, pipes, necklaces, swords, horns, fans, elephant tusks, leopard skins, terracotta pots, and dishware. All of this was used to assert the chief’s power. Beadwork and masks are common in this tribe. Masks were decorated with copper, cowrie shells, and beads. They were carved to represent male and female heads, stag, buffalo, birds, and elephant. The elephant masks and the buffalo masks represented power and strength.

With thanks to extracts from www.forafricanart.com

Shwe Shwe Textiles

Shweshwe cotton fabric expresses a cultural heritage of South Africa. It tells of the changing traditions of African Customary Dress over a period of time. Such developments can be attributed to both missionary and “western” European influences.

of time. Such developments can be attributed to both missionary and “western” European influences.

The presence of “indigo cloth” in South Africa has a long and complex history. Its roots probably extend as far back as early Phoenician and Arab Trade along the eastern seaboard before 2400BC. (Natural indigo dye was obtained from the Leguminous Genus, Indigofera plant).

However, it is known that after the 1652 establishment of a sea port at the Cape of Good Hope, indigo cloth arrived in South Africa from India and Holland. Slaves, soldiers, Khoi-San and Voortrekker women were clothed in indigo material and there is also evidence of floral printed indigo cotton.

During the 18th-19th centuries, European textile manufacturers developed a “block & discharge” printing style on indigo cotton fabric. and much of this cloth entered the South African market at this time. In the early 1840’s French missionaries presented the famous Sotho King Moshoeshoe 1st with a gift of indigo printed cloth establishing a cloth preference that grew during the 19th century and still prevails today, hence the term “shoeshoe” or “isishweshwe”.

Isishweshwe has a distinctive prewash stiffness and smell: this is inherent in its production and history, when during the long sea voyage from England to South Africa, starch was used to preserve the fabric from the elements and gave it its characteristic stiffness. After washing, the stiffness disappears to leave behind a beautiful soft cotton fabric. (Perhaps the name is derived from the swishing sound this starchy fabrics makes as this wearer walks along.

German settlers to the Eastern Cape in 1858 often elected to wear the “blue print” that was widely available as a trade cloth and echoed the “Blaudruk” (literally means blue print) that they were familiar with in Germany.

Shweshwe hearts

Xhosa women gradually added what they termed “Ujamani” to their red blanket clothing. These mission-educated African women absorbed European clothing styles enjoying the blue hue that the indigo gave their skin.

Such was the demand for the fabric that eventually there were four companies producing this print style, the largest being Spruce Manufacturing, who produced the most popular brand name “Three Cats” which was exported to South Africa.

Typical use in South Africa has been for traditional ceremonies in rural areas, thereby ensuring a constant demand for Shweshwe. In certain cases, special designs are produced for important occasions such as royal birthdays and national festivals. Today this fabric has become fashionable beyond its traditional usage and praise must go to young South African designers for their renewed interest in this traditional national heritage.

The production of Indigo Discharge Printed Fabric in South Africa started in 1982 when Total (a UK based company) invested in Da Gama Textiles. Blue Print was then produced under the trademark of Three Leopards , the South African version of the Three Cats trademark. They also introduced new colour ways – a rich chocolate brown and a vibrant red. In 1992 Da Gama purchased the sole rights to own and print the branded Three Cats range of designs and had all the copper rollers shipped out from England to the Zwelitsha plant in the Eastern Cape.

Da Gama still produces the original ‘German Print’, ‘Ujamani’ or ‘Shweshwe’ at the Zwelitsha factory. The process is still done traditionally, where the fabric is passed under copper rollers which have the patterns etched on the surface allowing the transfer of a weak discharge solution onto the fabric. Subsequent unique finishing processes create the distinctively intricate all-over prints and beautiful panels.

(Extracts derived and adapted from Da gama Textiles’ brief history)

Telephone Wire Products

Crafting from colourful wire, otherwise used in telephone cables can be as simple as child’s play or as complex as master craftsman weaving technology. In South Africa, children grow up making bangles and bracelets out of what they call  “scoobydoo”. However, below is a history of how this material has been transformed into high quality décor and fashion items.

“scoobydoo”. However, below is a history of how this material has been transformed into high quality décor and fashion items.

About the History & the Weaving Techniques:

Some say that the telephone wire basketry skill was innovated by master weaver Elliot Mkhize in the early 1970’s. While grass basket weaving is a craft passed down through tradition in the Zulu culture, the specific telephone wire weaving is a more recent development. Nowadays, the groups of wire weavers are numerous and still growing, as wire baskets become more and more popular worldwide. Most weavers today are men and women who have had no previous weaving skills, but learnt the skill of basket weaving as a necessity due to unemployment.

The story goes, that the origins of telephone wire is traced to Zulu night watchmen in the Durban area who – to fight loneliness and boredom on night shifts – took to weaving coloured  telephone wire around their traditional sticks. Soon this technique was adapted to making the Zulu beer pot covers, and wire plates. Today, this craft has developed hugely in creativity and diversity of uses.

telephone wire around their traditional sticks. Soon this technique was adapted to making the Zulu beer pot covers, and wire plates. Today, this craft has developed hugely in creativity and diversity of uses.

This coiling technique is unique to the greater Durban area. The designs that were used were inspired by the famous and exceptional Zulu beadwork patterns. Subsequently, the craft extended to include figures and text, usually depicting objects or animals in the crafters daily lives.

The “hard wire” plates are made differently. The wire is wound around the core wire in outward circles – from the inside out. This technique is much harder on the fingers and requires more skill and therefore the items are much more expensive.

Most of the wire weavers come from informal settlements and rural areas of South Africa. The informal settlements are comprised of very basic houses made of any available building materials, ranging from sheets of old corrugated iron to driftwood as well as cardboard. Some luckier residents have proper houses made of bricks. Many still live in very temporary type structures with no electricity, running water or sewage systems. The rural weavers live in mud huts and few have access to running water. Very few of the weavers have had a formal education – although their children are now attending schools.

The children are taught skills from a young age and are encouraged to try their hand at weaving as a hobby, as it is a way  to maintain and perpetuate their tradition of hand crafting, which is embedded in the Zulu culture. However, they do not participate in the art of weaving for commercial purposes at all.

to maintain and perpetuate their tradition of hand crafting, which is embedded in the Zulu culture. However, they do not participate in the art of weaving for commercial purposes at all.

In Cape Town, wire crafters have started integrating telephone wire into their superb sculptures. It’s an ideal medium for creating colourful text and fine work, especially for companies who wish to incorporate their corporate logo into an item.